Rethinking Range Anxiety

This is going to sound crazy, but hear me out. There’s a lot of FUD (Fear, Uncertainty, Doubt) out there around EV refueling (aka charging), especially when it comes to road trips. I get it, the refueling model is very different, and you need to know that the model is different, to understand that looking at refueling an EV like you refuel an ICE vehicle is broken. The main goal here is to create a resource on the topic that I can share with my friends, family, and random YouTube commenters who don’t think that the rules of physics apply universally, but there’s also a secondary goal. To say I was wrong before.

Let’s start with the place where I was wrong. In a recent post I mentioned that road trips suck when it comes to EV ownership, and that is true, sometimes. Most of the suck is in the planning phase, but really only when you’re going to the edges of civilization. Other road trips, as we found out this summer, don’t suck at all. In fact, they are surprisingly easy. Perhaps even easier, if you ignore the planning bit, because of destination charging. We’ll get into more detail on that as we get further into it.

Change Your Mindset

Maybe the right analogy is to think about charging the car the same way you do your mobile device. You plug it in at night and wake up to a full charge. Or if you care about battery health/longevity, and your phone supports it, something in the 80-85% range. You don’t generally worry about charging it throughout the day. It’s not something you need to think about unless you’re planning a day of heavy use. On those days maybe you bring along a charger so you can plug in at the conference center, or airport, or whatever. Taking advantage of the time you’d be sitting around to top up the device. It’s not that different in that you very rarely need to make a special trip to a special place to plug it in. Doing that just because, would be crazy.

Some of this FUD is the fault of car reviewers who like ICE cars, are reflexively comfortable with how they work, and don’t understand that DC Fast Charging (DCFC) should be the aberration, not norm. To be clear, it’s not a bad thing to like ICE cars (I like them too) unless it blocks one’s ability to understand that just because EVs look like a duck, the refueling paradigm is not a duck. Unless they have an EV (or a welder) it’s unlikely that they have Level 2 (L2) charging at their house, or think about leveraging it when the vehicle is at rest. Because that’s not how ICE cars work. You have to go out of your way, to a special place, interact with a machine, and wait to get the go juice. This is an active activity, where 99% of the time refueling an EV should be a passive activity. It just happens when the car is idle, as long as you remember to plug it in.

When I drove an ICE car, a normal not-on-a-road-trip refueling stop took about 15 minutes. That includes the amount of time it took to go to a gas station (generally on another errand), get out of the car, interact with the pump (insert credit card + zip code), pump the gasoline, and get out of there. If I did that weekly, it adds up to about thirteen hours a year. Now, I spend somewhere in the neighborhood of zero minutes per week filling up my EV because we have a L2 charger at home. That story changes, sometimes, on a road trip, but looking at it in the context of “math problem” still makes it a clear success story.

If the only way you refuel an EV is at the DCFC, then of course it’s going to be inconvenient. Because there aren’t very many of them, which means you may have to go much further out of your way to interact with a machine, and wait, perhaps a little bit longer than you’d like to, to get the go juice. Or, potentially get to a place where there aren’t any; and then you’re screwed. This though, is an infrastructure problem.

[Most] Range Problems Are Infrastructure Problems

Nuance is hard. Nuance is also important if you want to accurately criticize a thing. So it really tweaks my toes when I hear a reviewer (or rando) prattling on about how EVs don’t work because “range”. We don’t often talk about range for an ICE car, or what happens to that range when it’s cold (spoiler, it also takes a big hit), because the infrastructure for refueling ICE cars is a fixed problem. Again, I know that nuance is hard, but the goal of reviewing a thing should be at least a little bit educational. There are places where an EV doesn’t work because the infrastructure really sucks, but there are also a lot of places where it works brilliantly because the infrastructure is good enough.

In most cases we don’t need more range, especially because getting more range in the short term largely means bigger batteries, and the battery is the largest factor in the environmental cost of the EV. Addressing “range anxiety” at the car is shortsighted, but I get it. It’s something you can do personally, if you have the cash. Fixing the infrastructure is a bigger challenge, but we’re getting there. If you drive major corridors it’s actually kind of solved, even for those without a Tesla. If you have a Tesla, it’s totally solved; enjoy your road trip.

This seems like a good place to add a couple of non-Tesla EV road trips into the discussion, so you can see how it worked in two real examples, with two real EVs.

I’m a planner, so when my daughter wanted to visit UM Ann Arbor, and Case Western in Cleveland, I went to work in A Better Route Planner. The image at the top is what I ended up with. It’s a little hard to see there, especially if you don’t know what you’re looking at, but it was ~830 miles with three DCFC, and a few L2 destination charges. If you think about DCFC like a trip to the gas station, three of them over ~830 miles isn’t bad, and we didn’t spend any amount of time charging at the DCFC that we wouldn’t have spent at the stop if we had taken an ICE vehicle.

L2 is where the magic happens though. Find a hotel with a charger, you can pull in with 20% and wake up with 100% in the battery. Mix in some parking garages with L2, and even if you can’t find a hotel with a charger (which was the case in Ann Arbor), when you’re wandering campus, or taking the official tour, you’re putting electricity in the car. Leveraging that down time to refuel is a passive activity, it costs you zero time, zero inconvenience, it’s just happens; and in most case you don’t even pay for the electricity directly.

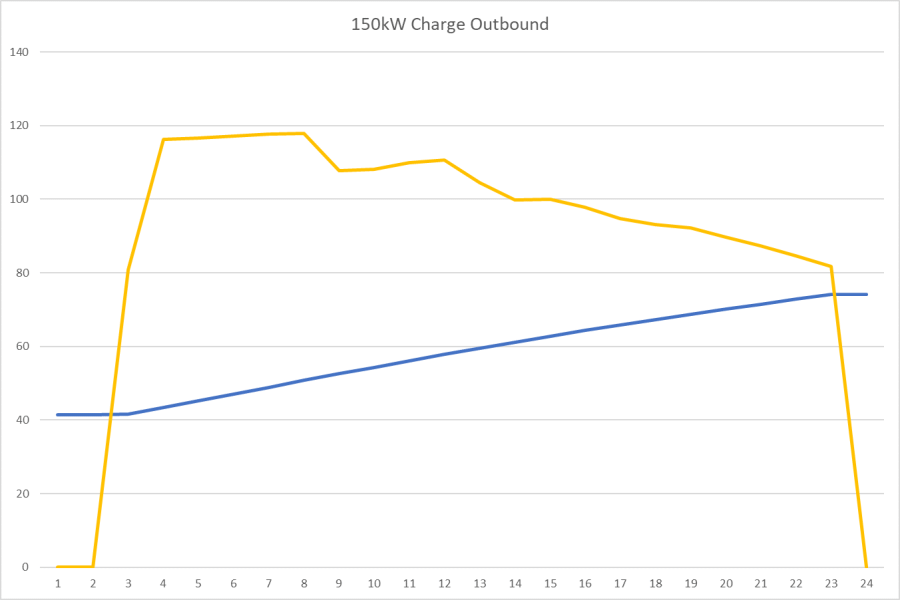

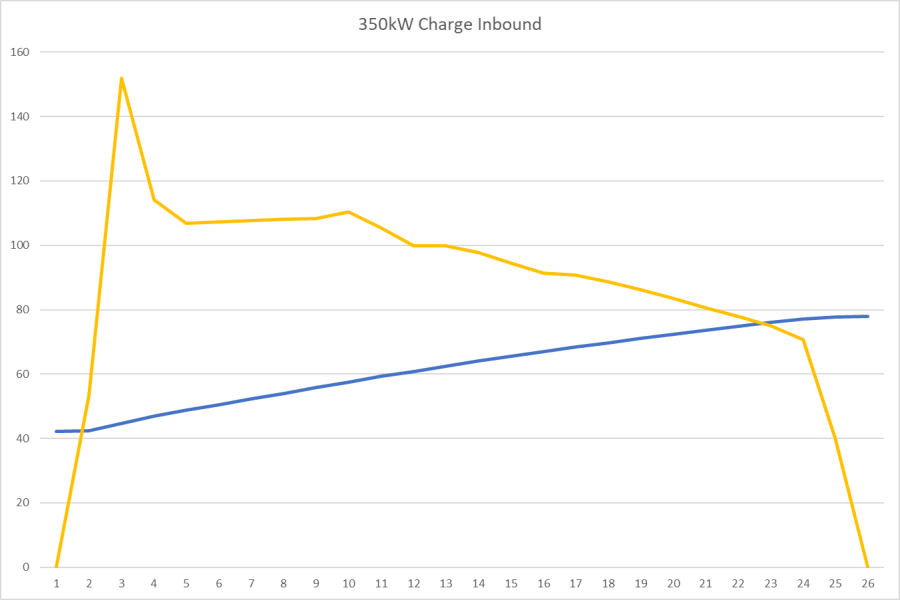

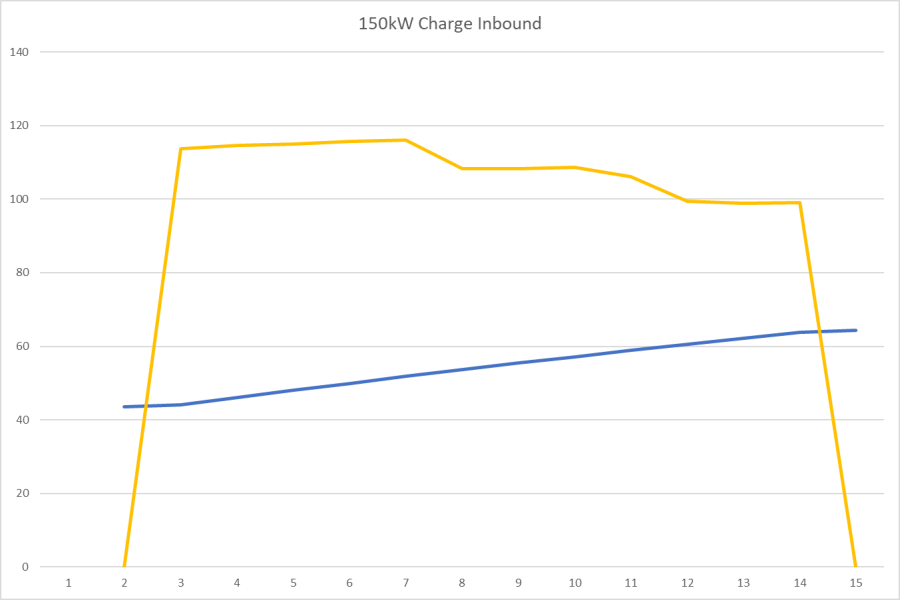

For the data geeks in the mix, I’ve included the charge curves for the three DCFC stops; in the order they were made. In all three cases, we stopped that long (24, 26, 15 minutes) because that’s how long we stopped to use the restroom, get a drink, snack, or in the case of the longest stop, eat an Impossible Whopper. Which wasn’t as bad as I’d feared.

Orange is kW, blue is State of Charge (SoC), and the x-axis is time in minutes.

The total cost of charging would have been ~$40, but because I still have Electrify America (EA) credit from Ford, we didn’t end up paying anything. Let me say that again, just so it doesn’t get lost, I paid $0 in electricity to drive ~830 miles.

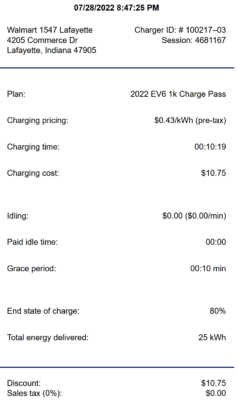

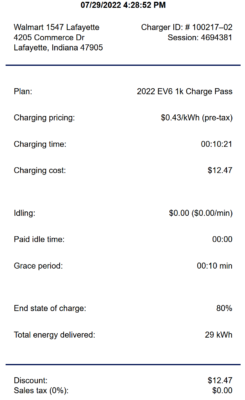

Obviously, those EA credits will run out at some point, and it’s quite possible that hotels and parking garages will start charging for L2. One of those things is fairly easy to work the math around. If you know that you’re going to go on a road trip, you can pay EA $4/month to drop ~$0.10 off the per-kW; which drops it from $0.43 to $0.31 at least around here. Which means that you will break even at a little over 30kWh.

My wife is not a planner when it comes to car travel, and I wasn’t going to explain how to use the OBD II dongle with Car Scanner to capture the charging data, so I’ve just included the receipts from EA from their trip to Bloomington, IN. Total charging time was 20 minutes, 40 seconds; at a cost of $23.22 (if we didn’t have EA credits).

In many ways this is a much better case study because it shows something closer to what a “normal” person would experience, albeit with one of the fastest charging EVs available currently. As long as they know to book a room at a hotel with L2 charging.

Infrastructure Is Still A Problem

Those are great examples, and if I just wanted to peddle a specific narrative it would be very easy for me to leave it there; with the success stories. But, they are only great stories because they were along major travel corridors with L2 destination charging options available. What happens if you want to go somewhere without great infrastructure? Well, that’s where it kind of sucks, but generally, you can still do it. If this sort of thing is a regular part of your travel use cases, then it could be a blocker, and that’s fair. We aren’t at a place where, even if we had the supply, an EV is the right answer for everyone. Here again though, this is an infrastructure problem, not a range problem.

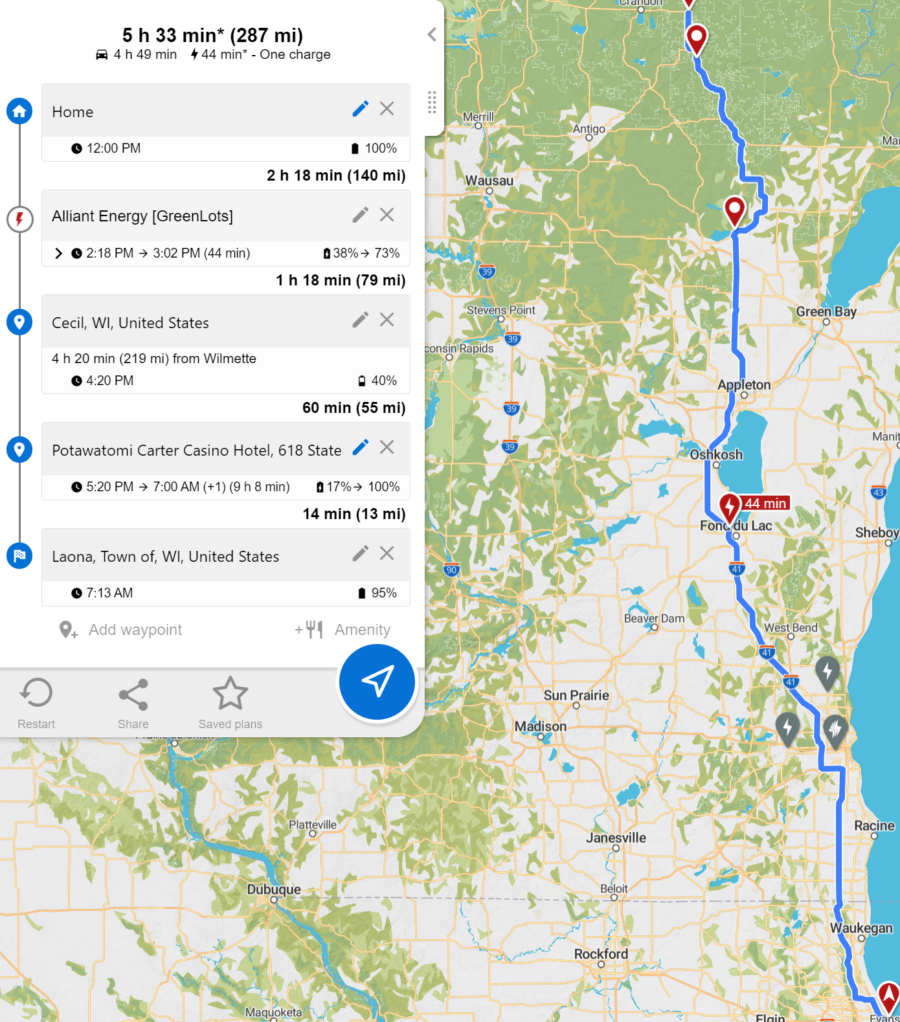

This is an example of a trip that I had to put some effort in to make work, and while there was a DCFC involved, it wasn’t fast (~45kW), so it took a while. It wasn’t a huge problem since I planned for it, but would have been nicer to cut that time in half.

Laona, WI is just south of the Michigan Upper Peninsula border, and a fairly rural area without many charging options. What made it work was that I was able to find a hotel with NEMA 14-50 RV hookups, so I brought along an EVSE and charged the car up when I got there. Going to the hinterlands is a challenge, and might be an insurmountable challenge. That sucks.

But, EA has a Green Bay, WI DCFC on their roadmap. When that comes online, whenever that is, it makes this headache mostly go away. Because, infrastructure :).

Finer Points

It should be clear at this point that charging your EV on a road trip doesn’t have to be a massive burden if the infrastructure is there. But, there are scenarios that are possible with an ICE car that aren’t really, even when good infrastructure is available. Do you want to drive 1,000 in one day; that’s possible in an ICE car if you hit the gas station strike team style, eat in the car, and generally make choices that optimize for speed over comfort. Although, having done that, and captured the data along the way I feel the need to point out that the “5 minute refueling stop” doesn’t exist; 10 minutes on the other hand is possible. If I can’t do that in a car with a 15 gallon tank, you can’t do that in a vehicle with a 34 gallon tank. Just saying…

The things that make that work are half infrastructure (there are gas stations wherever you want to stop, so driving the car to almost zero is possible), and half refueling speed. That extra 10-15 minutes to charge adds up over the course of a long drive, and since you don’t really want to charge past 80% in most EVs, the number of stops will be greater than when you let the range of an ICE take priority over comfort, and the need to pee. What is possible, but uncomfortable, with ICE become not really safe with EV.

The bigger question is whether that’s a common enough use case to offset the benefits over the rest of the year. Personally, for me, the answer is no. I’m not going to do that with my family in the car, and I might do that once a year. Obviously though, this is an individual math problem. So I would encourage everyone who actually does that, put the numbers in a spreadsheet and figure it out.

Some Range Problems Are Range Problems

Nuance bites again, because some range problems are actually range problems. Those are the hard ones to solve. The best example of this is towing. Despite what some people believe, this is a physics problem that impacts ICE vehicles as well. When you want to drag a heavy, blunt object through the air, there is a cost. It does seem to impact EVs more, by a small amount, probably because vehicle designers put some effort into aerodynamic efficiency with EVs, where they don’t seem to bother with their ICE counterparts. But, physics is physics. ICE trucks also take a massive hit to their range when they tow heavy, blunt objects. The difference is that this is an easy problem to solve on the vehicle side with ICE. Drop in a bigger fuel tank. Done.

It doesn’t matter that your range goes from 600 to 348 miles in the Silverado after you hook up the trailer, because most people aren’t going to drive 348 miles non-stop. But if they did, there would probably be a gas station wherever they were going (cough… infrastructure ;)). The starting range number is such a big number that it’s fine. That can’t be said for EV trucks even though they have massive batteries, because their massive batteries only get them to the 300+ miles place. Doubling that capacity, using today’s battery technology, isn’t going to work from a packaging or environmental perspective. And our discussion around the cumulative impact of charging costs obviously applies here as well, but worse because the range is so much lower.

Just like with cars there are scenarios where EVs don’t make sense, yet. If you regularly tow over 120 miles, especially to, or in, a remote location, that EV truck probably isn’t right for you. It’s likely to remain that way until battery technology improves, significantly. If you tow less frequently, or shorter distances, and go to places where you can DCFC along the way, or L2 when you get to where you’re going, they might be. This is a complicated problem with no right answer. And that’s fine. We live in a complicated world, with complicated problems, and complicated solutions.

That’s A Lot Of Words To Get To “It Depends”

This is one area that I struggled with when I was thinking about buying an EV, and it created a situation where I put off getting one far longer than I wish I had; knowing what I know now.

I wish it wasn’t this murky. I wish that when influencer type people talked about range, they took the time to understand it better, communicate it better, educate better. But complexity is hard, nuance is hard. There’s a good chance that many of the people who started this post TL;DR’d away by now, and I get that, but I don’t know how else to fix it besides yelling into the ether, so that’s what I’m doing. I wish that we could just agree to characterize “range anxiety” more appropriately as “infrastructure anxiety”.

An interesting / related article here : https://arstechnica.com/cars/2022/08/what-do-we-do-about-all-the-people-who-cant-charge-an-ev-at-home/ re. infrastructure, and the promoted comment reinforces your point.

This is the kind of range anxiety that is solved by infrastructure. If there was L2 where you parked the car, you would have been good. If there were more DCFC options along the way, you would have been good. This is the primary argument on the post (most range problems are really infrastructure problems).